Read this article about our school for this course: Hawthorne School to help Families in Need.

The article features one of our urban education students, Karen Rayburn!

Welcome!

This blog is the digital space where I reside online. This space is open to students, interested readers, and is a place where I share my adventures in reading, challenge the status quo, present ideas, and share new and captivating finds from the field of education and the wider world -- both on and offline.

Linda

I ask that if you have private questions to please email me at my University of Ottawa account rather than post here.

Linda

Saturday, 31 January 2015

Slammin' Across the Curriculum

What important implications slam

poetry has for youth writing in the “there and now” is one

of the questions Bronwen Low opens up to us in “Slammin’ School Performance

Poetry and the Urban School”? In this article, which was one of our readings

for this week, Low reads the rhetoric of the literacy crisis against what the

new literacies movement has revealed about adolescent literacies: that youth

feel compelled to speak through a range of related mediums such as slam poetry,

hip hop and social media. Turning the

idea of literacy being some sort of singular "entity" on its head, involves not only

working with different literacy modalities (reading and writing, texting, oral

traditions, video, for example), but also working to redefine what constitutes

literacies not as outputs (final products) but as practices.

Low, quoting Frith

(1983, p. 17) explains that “Black music is immediate and democratic – a performance

is unique and the listeners of that performance become part of it” (p. 78) From The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Slam

Poetry, we learn that “Slam poetry is the brainchild of Marc Smith (So What!)

and the blue collar intellectual eccentrics who crammed into the Get Me High

Lounge on Monday nights from November 1984 to September 1986 for a wide-open

poetry experience. Finger-poppin’ hipster Butchie (James Dukaris) owned the

place and allowed anything to happen, and it usually did. The experimenters in

this new style of poetry presentation gyrated, rotated, spewed, and stepped

their words along the bar top, dancing between the bottles, bellowing out the

backdoor, standing on the street or on their stools, turning the west side of

Chicago into a rainforest of dripping whispers or a blast furnace of fiery

elongated syllables, phrases, snatches of scripts, and verse that electrified

the night.”

A few questions and

thoughts to consider about teaching and slam poetry:

· When

we talk about digital storytelling or other tools to communicate, the concept

of audience is important.

·

Interesting

how slam poetry uses alternative literacy as a comment about the failings of ‘in-school’

traditional literacies.

“Trouble around

the text”: Fears that emerged in our discussion

·

Trouble

around assessment – how does assessing slam poetry different than assessing a

poem a student writes on the page. What

is inherent in performance that adds to the writing?

·

Location

: does it work in a rural setting?

·

How do

you evaluate a genre that is new to you as a teacher or that you might not

understand?

Slam Poetry in our class!

How does poetry about curriculum become globalized? In this case, we are reminded that the media is as much the message as the words being spoken. Low notes that “slam is the creation of its technologized context” (p. 78). Slam poetry reaches around the world via the internet.

Monday, 26 January 2015

Slip of the tongue

Here's a slam poetry example that students might identify with -- not just students in urban schools but everywhere. It could be a mentor text to speak to students about the concepts of colonialism, commodification, marketing, and relationships, as told by youth.

Mentor texts and the art and science of lighting fires through writing

This week in our class we are engaging with

the topic of mentor texts and are

taking up the questions of what are they, when would we use them, and why do

they matter? Reading along with this

topic Shelly Peterson’s (2008) chapter on Writing Non-Narrative in Content

Areas in Writing Across the Curriculum,

she explains that she uses the term “non-narrative instead of nonfiction” to

focus “on form rather than on whether or not the content is factual or imagined”

(p. 21). In this chapter, she provides a

range of examples of non-narrative forms and ideas for writing and provides

some useful mini-lessons on identifying features of genres that are meant to

inform, persuade or to instruct or direct.

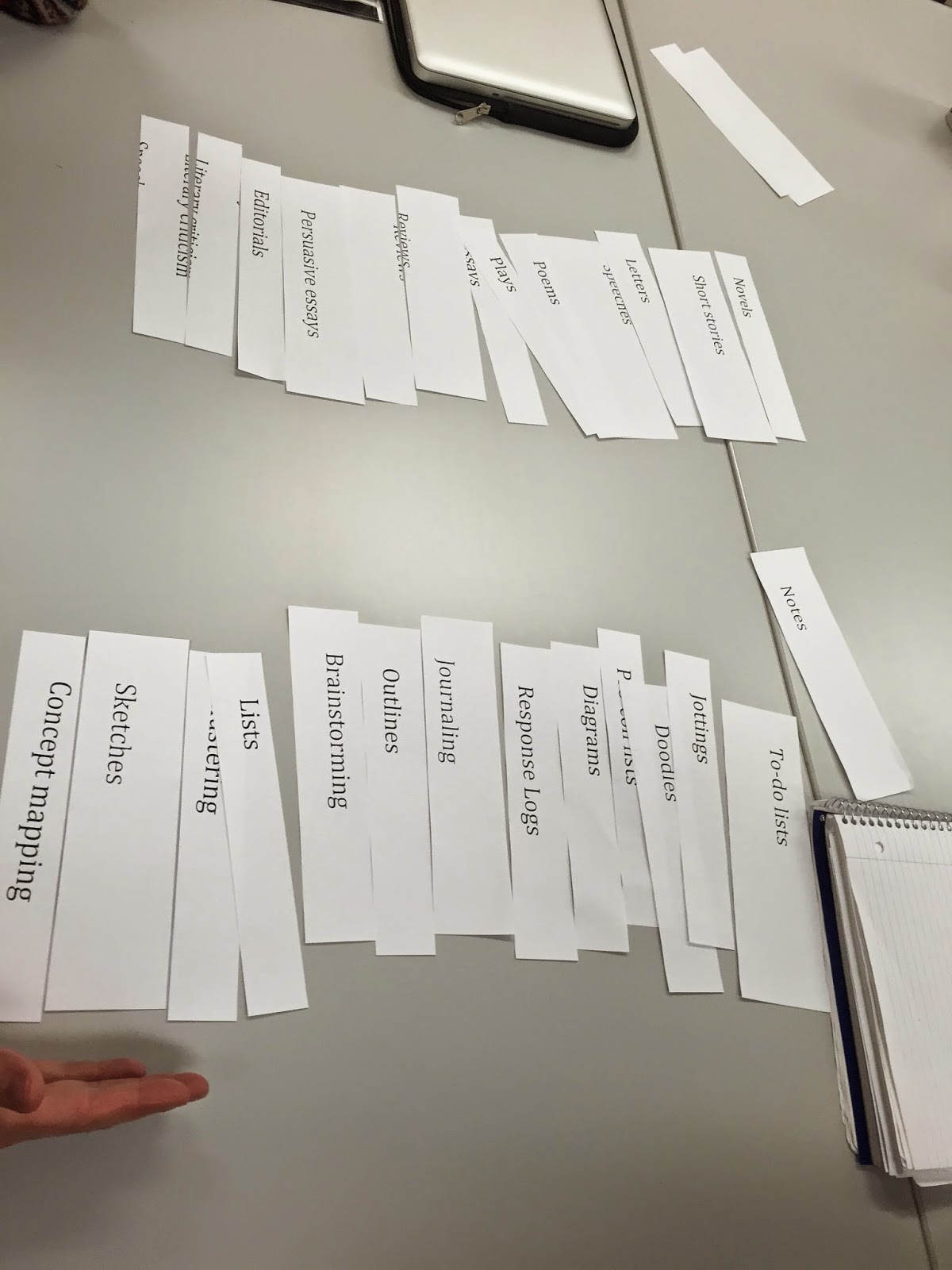

In our class today, we sorted through the

mentor texts you chose and we thought about the usefulness of such

classifications, as well as where some texts defied easy categorization. After brainstorming,

our class came up with key ways to use the mentor texts to help students learn about

different genres. Notable moments were finding websites that allow you to

adjust reading levels for informational articles, videos that exemplify

different approaches to introducing a concept, and the unique ways people put

their mentor texts on their blogs.

While the mentor texts you chose are for

your students, the mentor text I chose for you is about teaching. Roy F. Fox’s (1997) “Spiders, Fireflies and

the Glow of Popular Science” from Stephen Tchudi’s The Astonishing Curriculum: Integrating Science and the Humanities

Through Language is be a piece of non-narrative writing that is meant to

inform. I chose it because it is about a teacher who teaches writing through

what I would say is the most engaging way possible: by asking students to write

on a topic that fascinates them.

Fox begins his chapter with a little story

about the power of using sound to interact with mystery. He shares how he

begins with a poem about a firefly at a book club talk to discuss a collection

of poetry about nature. Asking his audience to choose their favorite poem from

the collection that all touched on some mystery, as he had done when he

selected the story about the firefly, the participants were fully engaged and

moved from reading their chosen poem to sharing what fascinated them and what

they remained curious about. Fox asserts, “teachers of many disciplines and

levels, from biology to art, from junior highs school to college, should ask

their students to select a mystery (which is somehow relevant to the course)

and write a descriptive popular science article about it” (p. 127). Taking up the topic of demystifying science

writing with integrating study of science, humanities and society, Fox encourages

us to develop teaching that immerses students in what is best about science:

“commitment, curiosity, discovery, focus, precision, knowledge and facts” (p.

128). “At the same time,” Fox writes, “students are absorbed in what is best about

the humanities: commitment, exploration, creativity, and clear communication

motivated only for purposes of sharing information” (p. 128). Arguing that

creating an assignment like “Writing a Popular Science Article” bridges the two

cultures, Fox underlines that the most significant element of the assignment is

personal, passionate curiosity. He notes that while experienced writers already

know what their passions are, students may not know, and, thus, they are the

ones who most need experience in the nurture between authentic involvement and

effective expression. Therefore, in his article, Fox shares his own process of

nurturing this dynamic by sharing his practice of having students get started

on their Make a Mystery Make Sense project and then engaging them in a range of

writing and oral response activities.

While at this point you may be thinking ‘okay,

there are some students who would run with this project but there are others

who are impossible to engage’, Fox shares that the hardest part of this

assignment is to help students discover the mystery that ignites them and “some

students never catch fire.” This is a tough situation, but Fox asks us to take

heart in at least helping students to understand that “personal fires feed real

inquiry” (p. 134). And, at least, this

is a beginning. As we continue to think

through teaching writing cross the curriculum, maybe holding onto this is also

a good beginning even while we strive to

create classrooms where writing to learn and learning to write will foster

passion and personal interest in the process of learning, which Fox exemplifies

through encouraging his students to interact with science in a humanizing way.

Saturday, 17 January 2015

Week 2: Blog Response and Summary to Atwell

“I want to go deep inside language together

and use it to know, shape and play with our worlds – but my practices evolve as

my students and I go deeper.” Nancie Atwell, In the Middle

In "Learning to Teach Writing," Atwell takes

us on a journey of how she began teaching as a creationist who focused on

creating curriculum to becoming an evolutionist who instead allows the

curriculum to unfold. She and her

students learn together and she teaches students what she sees they need to

learn.

While this first course reading for PED

3148 is specifically about teaching writing in the English Classroom versus

Writing Across the Curriculum, I chose it because it is above all else a

powerful story of learning. Beginning her story when she tells us “the gap was

at its widest with an eight grader who taught me that I didn’t know enough” (p.

4). Atwell describes how she moves from using a

highly prescribed, systematic ELA program that was accompanied by specific

behaviours she expected around learning and used “to manipulate students into

bearing the sole responsibility for narrowing the gap” (p. 4) of what they

didn’t know and what she expected them to learn. Sharing a story with us from

when she says the gap was at its greatest, we meet Jeff and eight grade student

who struggles with writing.

Instead of following the process of the prewriting

procedures, Jeff drew pictures and his sister helped him scribe his story at home. Despite what Atwell explains as her continual “strong disapproval” of Jeff’s approach, he persevered and was able to pass the course and move on to

high school. While it wasn’t only until years later that Atwell realized she

had to change her pedagogy to accommodate the behaviors of beginning writers

and not expect them to all find ways “to make sense of, or peace with the

language arts curriculum or ….to fail the course” (p. 4), it was the experience

of not being able to reach Jeff that became for her what Shoshana Felman calls

“trouble around the text.” In later reading what she revisited to learn when

Jeff was in her class, that sitting behind the big desk in the front of the

classroom and following a curriculum structure that prescribed topics and

insisted on a specific process, she held fast to the belief that her “ideas

were more credible and important than her students might possibility explain”

(p. 7).

Poignantly Atwell confesses what many

teachers may at some level know but defend against admitting: “I had missed the

chance to understand what I was doing to talk to him and learn from him how to

help him” (p. 9). Here the teacher becomes an interventionist (Taylor, 2000, p. 48) where turning away from a prescribed curriculum she moves to a writing

workshop model that allowed students choice in what they would write and how

they would write to later refining her pedagogy further “reintegrating the

teacher to central in the writing classroom” (Taylor p. 48). Using a backwards design strategy of sorts,

Atwell is direct in her approach of being very clear in her expectations and

what students are responsible to achieve. To support her students, Atwell uses

an apprenticeship model and uses what Jerome Bruner called the “handover”

method, also known as gradual release, as the teacher intervenes and gradually

provides less support for the learner to help students learn skills and

synthesize knowledge, as they become confident writers.

It is here that I see what we can learn

from Atwell’s story of learning and the sort of pedagogies we may want to adapt

when thinking about teaching writing across the curriculum. In building our own

knowledge based and use of instructional strategies that Peterson (2008) offers

in her text for teachers, we can begin to imagine what are the possibilities

for the diversity of writers in our classrooms.

Sunday, 11 January 2015

Recap from the first class!

Thank you all for a great first class!

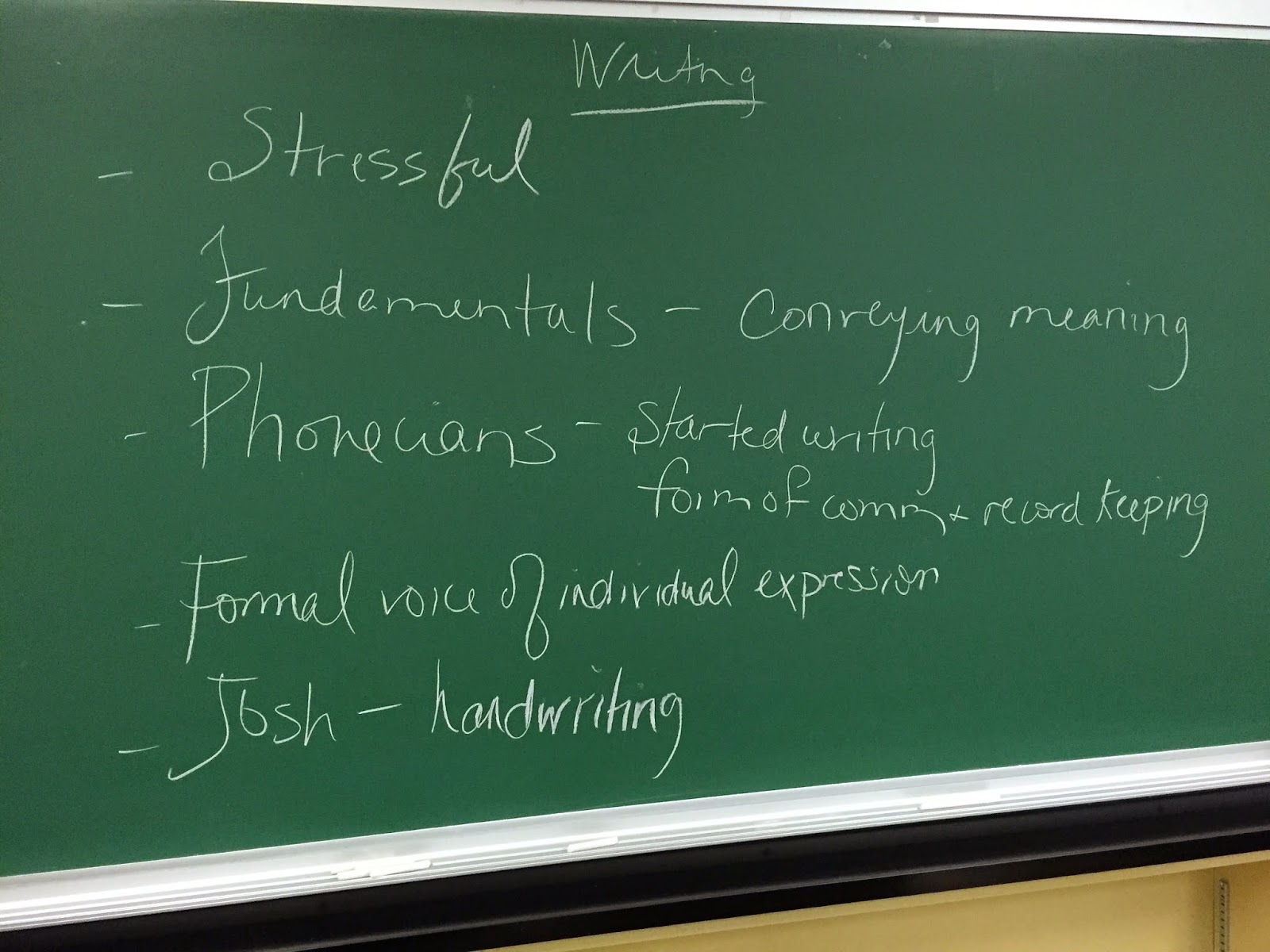

We gathered thoughts together about what comes to mind when you hear the word "writing." Your responses were interesting and varied. I have your ideas that we wrote on the board captured in the photos below. Thank you for sharing your free writing! I have shared my free-write below.

In-class free write - Linda Radford

What comes to mind when I hear the word writing? Sheer fear of whether not I can get what is in my head onto the page in a way that is coherent, readable, proactive, interesting, and important. Thus, in terms of putting words on the page, writing to me is a tall order that is accompanied by the anxiety of the work along with the delight of accomplishing what I set out to say. The other thought that comes to mind about writing is about reading. The joy and benefit I receive from reading the word, or as Freire contends, the world. Through reading what is represented, I can read myself with and against different texts and gain a deeper knowledge of who I am and my work in education.

We gathered thoughts together about what comes to mind when you hear the word "writing." Your responses were interesting and varied. I have your ideas that we wrote on the board captured in the photos below. Thank you for sharing your free writing! I have shared my free-write below.

In-class free write - Linda Radford

What comes to mind when I hear the word writing? Sheer fear of whether not I can get what is in my head onto the page in a way that is coherent, readable, proactive, interesting, and important. Thus, in terms of putting words on the page, writing to me is a tall order that is accompanied by the anxiety of the work along with the delight of accomplishing what I set out to say. The other thought that comes to mind about writing is about reading. The joy and benefit I receive from reading the word, or as Freire contends, the world. Through reading what is represented, I can read myself with and against different texts and gain a deeper knowledge of who I am and my work in education.

Sunday, 4 January 2015

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)